Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Identification Key

The Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) key was designed to allow you to identify most species of aquatic grasses found in Maryland. Although submerged aquatic vegetation is notoriously difficult to identify using standard taxonomic keys, the flexible format of the Internet allows us to combine detailed pictures, simple line drawings and text messages in a stepwise sequence that makes identifying SAV simple. You may find it useful to have a clear metric ruler with millimeters marked, a magnifying glass, and a Ziploc plastic bag to help you in the process of identifying your plant.

|

Use SAV Key |

|

If you already know the identity of a particular bay grass use the dropdown menu below: |

| Common Name (Scientific name): |

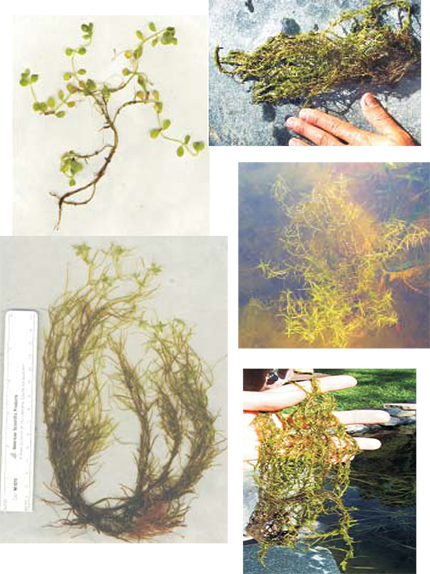

Bladderwort:

| Common Name: | Bladderwort | |

| Scientific Name: | Utricularia spp. | |

| Native or Non-native:: | ||

| Illustration: |  |

|

| Link to larger illustration: | ||

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. | |

| Family: | Lentibulariaceae | |

| Distribution: | Several species of bladderwort occur in the Chesapeake Bay region, primarily in the quiet freshwater of ponds and ditches but occasionally in the open water of lakes and reservoirs. Bladderworts can also be found on moist soils associated with wetlands. | |

| Recognition: | Bladderworts are found floating in shallow water or even growing on very moist soils. The stems are generally horizontal and submerged. Leaves are alternate, linear or dissected often appearing opposite or whorled. The branches are often much dissected, appear rootlike and have bladders with bristles around the openings. Bladderworts are considered carnivorous because microscopic animals can be trapped and digested in the bladders that occur on the underwater leaves. When the plant is flowering, it produces flowers with five petals that appear fused together and are often yellow in color. Some species have flowers that come well out of the water and are quite showy. | |

| Ecological Significance: | Even though bladderwort is a carnivorous plant, it can provide habitat and shelter for many macro and micro invertebrates, which in turn provide food for waterfowl and fish. Some of these microorganisms have been found to form symbiotic relationships with the bladderwort plants to help with the attraction and digestion of the plant's prey. | |

| Similar Species: | Coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum) | |

| Reproduction: | Sexual reproduction through many seeds that each plant releases when mature. |

Common Waterweed

| Common Name: | Common Waterweed |

| Scientific Name: | Elodea canadensis |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Hydrocharitaceae |

| Distribution: | Common waterweed is primarily a freshwater species, and occasionally grows in brackish upper reaches in many of the Bay's tributaries. It prefers loamy (sandy and silty) soil, slow-moving water with high nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations. |

| Recognition: | The leaves of common waterweed can vary greatly in width, size and bunching. In general, the leaves are linear to oval with minutely toothed margins and blunt tips. Leaves have no leaf stalks, and occur in whorls of 3 at stem nodes, becoming more crowded toward the stem tips. Common waterweed has slender, branching stems and a weak, thread-like root system. |

| Ecological Significance: | Common waterweed prefers silty sediments and nutrient rich water, where it is sometimes perceived as a nuisance. However, it will grow in a wide range of conditions, from very shallow to deep water, and in many sediment types. It can even continue to grow unrooted, as floating fragments. It is found throughout temperate North America. Common waterweed is an important part of tidal and nontidal freshwater ecosystems. It provides good habitat for many aquatic invertebrates and cover for young fish and amphibians. Waterfowl, especially ducks, as well as beaver and muskrat eat this plant. Also, it is of economic importance as an attractive and easy to keep aquarium plant, but cannot just be taken out of a stream or lake and into an aquarium. |

| Similar Species: | Common waterweed resembles hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata). Hydrilla, however, has prominent teeth on leaf margins with leaves occurring in whorls of 3-5. Underwater common waterweed resembles the water starworts (Callitriche spp.); however its leaves are in whorls of 3 whereas those of water starwort are in pairs on stem nodes. The very similar Western waterweed (Elodea nuttallii) is reported to occur in the Chesapeake Bay (Brown and Brown, 1984) but its identification (and thus its distribution) are poorly known. Elodea nuttallii may have a higher salinity tolerance (up to 10 ppt) than common waterweed. Brazilian waterweed (Egeria densa) has also been reported in the Bay, but its distribution is poorly known. |

| Reproduction: | Common waterweed reproduces sexually and asexually. Common waterweed is dioecious and, with the female form being more abundant than the male, sexual reproduction is rare. Sexual reproduction produces cylindrical fruit capsules. Asexual reproduction is common and occurs by stem branching, growth buds of stem fragments, and by spring development of over-wintering structures laterally. |

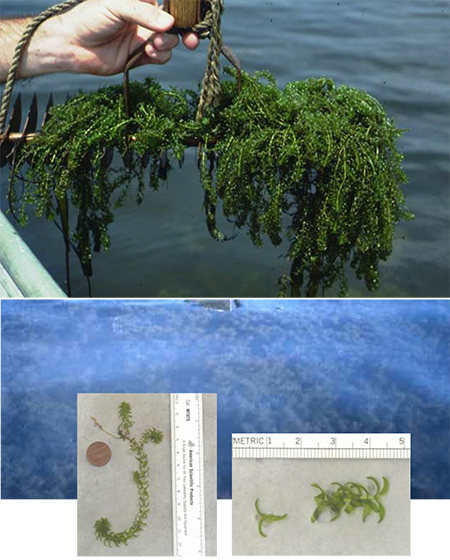

Coontail, Hornwort

| Common Name: | Coontail, Hornwort | |

| Scientific Name: | Ceratophyllym demersum | |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay | |

| Illustration: |  |

|

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

|

| Printable Version: | ||

| Family: | Ceratophyllaceae | |

| Distribution: | Coontail (also commonly known as Hornwort) is cosmopolitan in the Mid-Atlantic, and usually grows in freshwater reaches of tributaries, lakes or ponds with moderate to high nutrient concentrations. The stiff, brushy growth of coontail is fragile and as such it is limited to slow moving water. It can also be found in the interior of large beds composed of other bay grass species. Unlike other SAV, coontail has no true roots and it can grow free-floating. Because of its ability to absorb enough nutrients from the water column, coontail can grow in any substrate. | |

| Recognition: | Coontail, because it has no true roots, may float in dense mats beneath the water surface and is only occasionally attached to the sediment by its basal ends. Coontail has slender, densely branched stems of up to 2.5 m (9 ft) in length. The compound leaves of coontail are divided or forked into linear and flattened segments 1 cm to 3.5 cm (2/5 in to 1 3/5 in) long with fine teeth on one side of the leaf margin. Leaves have a stiff and brittle texture and grow in whorls of 9 to 10 at each stem node with whorls becoming more crowded towards the stem tips. | |

| Ecological Significance: | Coontail is found in all 50 states and Puerto Rico. Unlike the other bay grasses found in the Chesapeake Bay, coontail has no true roots and obtains all its nutrients directly from the water column. It is very shade tolerant and can form large, dense mats in tidal freshwater tributaries of the bay and in slow-moving streams and ponds. These dense mats can provide habitat for small fish, aquatic animals, and aquatic insects. Coontail can also be eaten by some waterfowl, but it is not an important food source like other species of SAV. Also, since Coontail is so good at absorbing nutrients from the water, it can provide water quality benefits in areas with unconsolidated sediments where no other SAV can grow. | |

| Similar Species: | Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) has roots and pinnate leaves and is very different in form from coontail, appearing more feathery and limp when held out of the water. | |

| Reproduction: | Coontail reproduces asexually (vegetatively) and sexually (by seed). Stem fragments with lateral buds develop into new plants throughout the season. In autumn stem tips break off and over-winter on the bottom before sprouting in spring. Occasional sexual reproduction produces small purple flower clusters between July and September, followed by a single nut-like seed. Shade-tolerance and its floating habit make turbidity less of a limiting factor for coontail than for other bay grasses. |

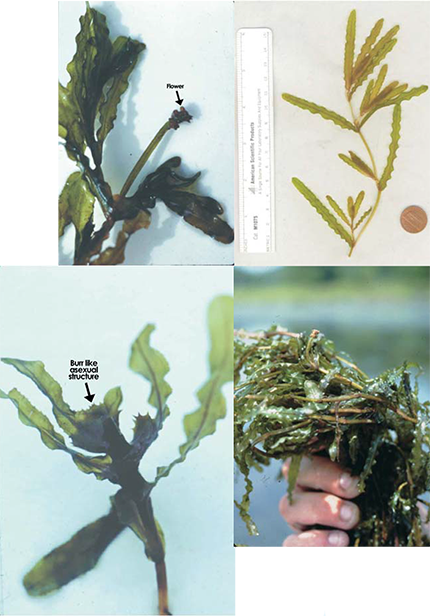

Curly Pondweed

| Common Name: | Curly Pondweed | |

| Scientific Name: |

|

|

| Native or Non-native: | Non-native | |

| Illustration: |  |

|

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

|

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. | |

| Family: | Potamogetonaceae | |

| Distribution: | Curly pondweed grows in fresh non-tidal to slightly brackish tidal waters. Curly pondweed is thought to have been introduced from Europe in mid-1800's; today it has worldwide distribution and is widely distributed in streams, rivers and reservoirs of the Chesapeake Bay. | |

| Recognition: | Perhaps the most easily recognizable species in the bay, with robust leaves 3 cm to 10 cm (1 ¼ in to 4 in) long, broad, linear and finely toothed, with undulated(curly) margins. Leaves are arranged alternately or slightly opposite on flattened, branched stems. Roots and rhizomes are shallow, and not as extensive as in other bay grasses. Vegetative buds sprout in the fall and the winter form of the plant develops with blue-green leaves that are more flattened. In spring, the spring/summer form appears with reddish-brown leaves that are wider and curlier. Flowering occurs in late spring or early summer and the plants begin to die-off in midsummer after the vegetative buds are produced. The buds remain dormant until fall, when the cycle is repeated. | |

| Ecological Significance: | Curly pondweed is an introduced species that is widespread throughout the U.S. While not normally problematic in tidal waters, curly pondweed can be invasive when it occurs in lakes and reservoirs. Curly pondweed provides food for ducks and is particularly valuable winter and spring habitat for fish and invertebrates due to its ability to grow when waters are too cool for many other aquatic plants. | |

| Similar Species: | Curly pondweed may resemble young shoots of redhead grass (Potamogeton perfoliatus), but the leaves of redhead grass are typically shorter and wider. | |

| Reproduction: | Plants reproduce through extension of rhizomes, development of burr-like asexual structures near stem tips, and by seed development from flowers that float at water surface atop spikes. The curly pondweed life-cycle has a three-stages: winter form, spring/summer form, and dormant vegetative (asexual) bud. |

Eelgrass

| Common Name: | Eelgrass |

| Scientific Name: | Zostera marina |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Zosteraceae |

| Distribution: | Once one of the most abundant and most persistent bay grass species in the high-salinity portions of Chesapeake Bay and the lower tributaries, ranging from the Miles River south to the mouth of the bay. Most eelgrass in Maryland has disappeared due to increasing water temperatures in the bay. Eelgrass can now only be found in Tangier Sound south to the mouth of the bay and in the lower reaches of very high salinity tidal rivers. |

| Recognition: | Eelgrass has a thick creeping rhizome 2 to 5 mm (1/16 in to 1/8 in) with numerous roots and a leaf at nodes spaced 1 to 3.5 cm (1/3 in to 1 ½ in) apart. Alternate, ribbon-like leaves with rounded tips arise from these nodes and grow to 1.2 m (4 ft) in length and 2 to 12 mm (1/16 in to 1/3 in) width. Each leaf has a tubular, membranous basal sheath 5 to 20 cm (2 in to 8 in) long and with a width greater than that of the leaf itself. The leaves are relatively small and narrow where the plants grow on shallow, sandy, physically exposed substrates. Longer, wider leaves occur on plants growing on deep, muddy, and exposed areas. |

| Ecological Significance: | Eelgrass is the only true “seagrass” found in the Chesapeake Bay. Eelgrass occurs along both coasts of the United States, and the Chesapeake Bay is near the southern limit of its distribution on the east coast. Unlike other bay grasses, eelgrass dies back during the warm summer months and grows best in the cooler waters of spring and fall. Eelgrass is an important habitat for blue crabs that use the beds for protective cover during mating and as juveniles. It is also an important habitat for the seahorse, pipefish and speckled sea trout, and important food source for brant geese (which almost disappeared when the eelgrass declined significantly in the 1930s due to the “wasting disease”). Canada geese, widgeon, redhead and black ducks and green sea turtles all feed on eelgrass. Eelgrass also provides a spawning site for some species of fish, and can also reduce coastal erosion by securing the sediment with its roots. |

| Similar Species: | The basal form of widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima) can be mistaken for eelgrass, though the former has thinner and longer leaves. Eelgrass can also be mistaken for wild celery, and looks so similar that some call wild celery “eelgrass” even though the two are different. |

| Reproduction: | Eelgrass reproduces asexually and sexually. Asexual reproduction occurs through growth and elongation of the rhizome and by formation of turions. Sexual reproduction occurs through seed formation, and begins with flowering in May and June. Eelgrass is monoecious and fertilization occurs by drifting pollen. Male and female flowers mature at different times on the same plant to prevent self-fertilization. Once fertilized the flowers develop into seed-bearing generative shoots that eventually break off and float to the surface. The shoots then release their seeds as they drift. |

Eurasian Watermilfoil

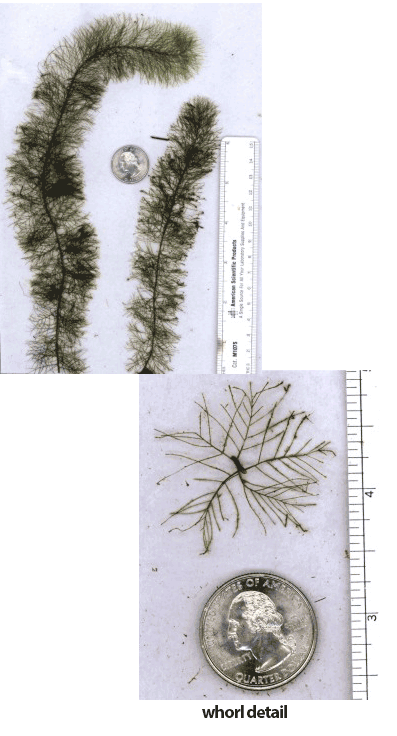

| Common Name: | Eurasian Watermilfoil |

| Scientific Name: | Myriophyllum spicatum |

| Native or Non-native: | Non-native |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Haloragaceae |

| Distribution: | Introduced from Europe and Asia, Eurasian watermilfoil is now found throughout the United States. Explosive growth of Eurasian watermilfoil during the late 1950's covered large areas of the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries. Eurasian watermilfoil choked waterways until the infestation came to an end in the early 1960's, possibly due to spread of a virus-like organism in combination with pollution, grazing, and herbicide and harvesting programs. Eurasian watermilfoil is still present in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries today, inhabiting non-tidal fresh to moderately brackish tidal water. Eurasian watermilfoil is often the first species to appear in the spring in tidal tributaries with fairly degraded water quality and may be followed by other native species. Eurasian watermifoil is also one of the last species of SAV to die back in the fall, often retaining aboveground biomass through December. |

| Recognition: | Up to 2.5 m (9 ft) tall, leaves in whorls of 4 or 5, finely divided (pinnate), 0.8 cm to 4.5 cm (1/3 in to 2 in) long with 9 to 13 hair-like segments per side. When removed from water these delicate leaves compress and lose their shape. Lower portions of the stems may be devoid of leaves. |

| Ecological Significance: | Eurasian watermilfoil is not considered a great food source for waterfowl but it provides excellent cover for young fish, crabs and invertebrates. Fishermen recognize watermilfoil beds as excellent places to catch largemouth bass, which are often found lying in ambush near watermilfoil plants. |

| Similar Species: | Eurasian watermilfoil usually has whorls of 4 pinnate leaves whereas parrot feather (Myriophyllum brasiliense) usually has whorls of 5 pinnate leaves. Appearance is similar to coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), however, coontail has whorls of 9 to 10 leaves at stem nodes, has stiffer leaves (especially when taken out of the water), and lacks a root system. |

| Reproduction: | During late summer watermilfoil grows flower spikes on stem tips that protrude above the water surface. Self-pollination does not occur because the pistillateflowers on each individual reach maturity before its staminate flowers. Aerial pollination produces nut-like fruits that sink to the bottom where they can remain viable for years. Asexual reproduction occurs by fragmentation. |

False Loosestrife

| Common Name: | False Loosestrife |

| Scientific Name: | Ludwigia sp. |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Onagraceae |

| Distribution: | Common on the Coastal Plain and occasionally throughout Chesapeake Bay along the shores of freshwater streams, rivers and ponds. This plant is located in other parts of the USA as well, with the highest concentration in the Midwestern states. This is an emergent terrestrial plant, but one that can grow underwater for many weeks and is thus often confused for SAV. |

| Recognition: | Grows to 1 meter tall, leaves usually linear to lanceolate 1 to 6 cm long, alternate or opposite. The stems are light green to pink, and are generally sparsely branched towards the bottom. Flowers July to September and produces flowers that are light green to pink with 4 lobes and up to 4 petals. Petals are not often present, but when they are they are green/greenish yellow and 1-2mm in length. The most distinctive part of the plant are its fruits which have four sides and four sepals at the top of each fruit. |

| Ecological Significance: | The flowers provide nectar and pollen to insects, and the leaves of the plant are fed on by other insects |

| Similar Species: | None |

| Reproduction: | Reproduces by seed. The flowers can self-pollinate if no insects aid in the pollination process, and then the fruits are split open containing many very small seeds, which are blown by the wind or carried by water. |

Horned Pondweed

| Common Name: | Horned Pondweed |

| Scientific Name: | Zannichellia palustris |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Zannichelliaceae |

| Distribution: | Zannichellia palustris, or horned pondweed, is found in every state in the continental United States, as well as in Europe and South America. Horned pondweed is widely distributed in Chesapeake Bay, growing in fresh to moderately brackish waters, in muddy and sandy sediments. Horned pondweed seems to grow most abundantly in very shallow water but may grow to depths of 5m (16.4 ft) given enough light. Horned pondweed is an annual plant and is one of the first bay grasses to appear in the early spring. By June as water temperatures warm, the plants release their seeds and die back. Two growth forms of horned pondweed are found in the bay, one upright and the other creeping, the latter of which is found in areas of higher wave energy. |

| Recognition: | Long, linear, thread-like leaves are mostly opposite or arranged in whorls on slender branching stems. Leaf tips gradually taper to a point, and a thin sheath or stipule covers the basal parts of leaves. Horned pondweed has tendril-like roots and slender rhizomes. The seeds of horned pondweed readily distinguish this species and occur in groups of 2 to 4, are horned shaped and form in the leaf axils. |

| Ecological Significance: | Horned pondweed provides food and habitat for many species of macro and micro-invertebrates, and these species are in turn eaten by species of fish, amphibians, waterfowl, etc. Waterfowl also commonly eat the plant and its seeds. Horned pondweed may have unique value to some organisms as it is present much earlier in the year than most other species. |

| Similar Species: | Sago pondweed (Studkenia pectinata) and widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima) are similar in appearance to horned pondweed. Sago pondweed, however, has leaves in bushy clusters, and widgeon grass has alternate leaves, whereas horned pondweed has opposite or whorled leaves. The species are easily distinguished when they are in seed. Widgeon grass has single seed pods that form at the base of fan-shaped clusters of short flowering stalks. Sago pondweed seeds are in terminal clusters. Horned pondweed has distinctively (horned) shaped seeds that occur in the leaf axils in groups of 2 to 4. By the time sago pondweed and widgeon grass appear, horned pondweed usually is covered with seeds. |

| Reproduction: | Two growth forms of horned pondweed occur in Chesapeake Bay: 1) an upright form with free-floating branches, and 2) a prostrate or creeping growth form with stem node roots that anchor the plant in areas with high wave energy (also common form in winter). Horned pondweed is usually the first bay grass to appear in spring, and seed formation occurs in early to late spring. Reproduction is mostly by seed formation; the seeds are horn-like, slightly curved fruits that occur in groups of 2 to 4. Decline usually begins in June or early July, and produces floating mats of decaying plants. Thereafter, a second growth cycle can occur in fall, and it can grow over the winter in some areas. Horned pondweed seeds generally germinate in the same year as seeds are set. |

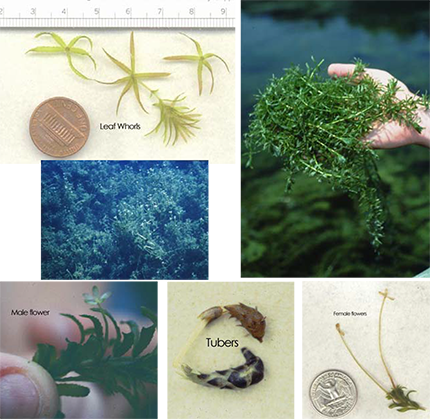

Hydrilla

| Common Name: | Hydrilla | |

| Scientific Name: | Hydrilla verticillata | |

| Native or Non-native: | Non-native | |

| Illustration: |  |

|

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

|

| Printable Version: | ||

| Family: | Hydrocharitaceae | |

| Distribution: | Hydrilla is an exotic species introduced from southeast Asia which first appeared in the United States in the 1960's. Today it is found in most of the southeastern United States, westward to California. Hydrilla was first observed in 1982 in the Potomac River near Washington D.C. and by 1992 grew to cover 3,000 acres in the Potomac. Fears that hydrilla would take over and permanently alter the Potomac ecosystem proved to be unfounded, as many of the areas that hydrilla expanded into were subsequently colonized by a host of native species. Hydrilla is now cosmopolitan in the mid-Atlantic, and is found in streams, ponds, lakes and both tidal and non-tidal rivers throughout Maryland. Hydrilla is predominantly a freshwater species, but has been found in waters of 6-9 ppt salinity. Hydrilla prefers silty to muddy substrates and tolerates lower light than other bay grass species. | |

| Recognition: | Stems are freely branching with whorls of 3-5 leaves linear to lanceolateleaves. Leaves have strongly toothed or serrated margins and a spinous midrib. Roots are adventitious, forming along nodes of rhizomes that grow horizontally atop or just below sediment surface. Tubers are also commonly found at the end of runners that branch from the buried rhizome. | |

| Ecological Significance: | Hydrilla is an introduced species first identified in the Chesapeake Bay region in 1982. It is often considered a nuisance plant because of its habit of forming dense impenetrable beds that impede recreational uses of waterways. Because of the substantial populations of hydrilla found in the Potomac River when it first appeared, a mechanical harvesting program was instituted to keep the many marinas along the river open to boat traffic. Since that time hydrilla has gone through boom and bust cycles in many rivers, usually falling in abundance to the point where it's no longer a significant impediment to water contact recreation within a few years. Hydrilla is an excellent food source for waterfowl and provides excellent fish habitat. | |

| Similar Species: | Common waterweed (Elodea canadensis) has a similar appearance, however, leaves of waterweed are in whorls of 3 and are not as markedly toothed as those of hydrilla. Common waterweed also lacks the tubers that hydrilla forms in late summer or early fall. | |

| Reproduction: | Hydrilla reproduces sexually and asexually. The strain found in Chesapeake Bay is monoecious, with male and female flowers occurring together near the growing stem tips. Small, white female flowers are born on a hypanthium at the water surface. Male flowers detach from stem tips and float to the water surface. The pollen they release must settle directly on the female flower for pollination to occur. Seed set has never been documented in hydrilla in Chesapeake Bay. Asexual reproduction occurs through fragmentation, production of new stems from rhizomes, turions (resting plant buds that develop in leaf axils or tips of branching stems) which break off then sink to the substrate and form a new plant, and tubers (another type of resting plant bud) that develop at ends of buried runners that branch off from rhizomes. Tubers and turions can over-winter and are the major form of reproduction in the mid-Atlantic region. |

Illinois Pondweed

| Common Name: | Illinois Pondweed | |

| Scientific Name: | Potamogeton illinoensis | |

| Native or Non-native:: | ||

| Illustration: |  |

|

| Link to larger illustration: | ||

| Printable Version: | ||

| Family: | Potamogetonaceae | |

| Distribution: | Unknown. Not certain if this species exists in Maryland. It can survive in lakes and rivers, and in shallow or deep water. | |

| Recognition: | A large, broadleaf SAV species with very large two-keeled stipules. | |

| Ecological Significance: | Used as a food source by waterfowl, and provides habitats for micro and macro invertebrates. Can cause problems for other plants by blocking out sunlight when it forms dense mats, and can also reduce water temperature and oxygen concentrations. | |

| Similar Species: | Other Potamogeton species. | |

| Reproduction: | Sexual reproduction by seed. |

Low Watermilfoil

| Common Name: | Low Watermilfoil |

| Scientific Name: | Myriophyllum humile |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | |

| Distribution: | Native to Chesapeake Bay, but rare. Found mostly in the shallow waters of coastal ponds and reservoirs. The plant also tends to grow better in more acidic waters. |

| Recognition: | Plant stems are very leafy, and stay submersed in the water. Leaves usually in whorls of 5 (mostly subopposite or scattered), all alike, 1-2.5 cm long with 6-10 hair-like segments per side. The leaves themselves are very slender and skinny, and make feather-looking groups. The stem of the plant can sometimes take on a reddish appearance, and sometimes the leaves can get this color as well, instead of their usual green appearance. |

| Ecological Significance: | Just like Eurasian Watermilfoil, Low Watermilfoil can provide habitat for small organisms, such as young fish and small invertebrates, in the ponds and reservoirs that it inhabits. |

| Similar Species: | Coontail (coarse, roughly divided leaves), and Eurasian Watermilfoil. The difference between Eurasian Watermilfoil and Low Watermilfoil is that Eurasian Watermilfoil only has whorls of 4. |

| Reproduction: | Sexual reproduction through seeding, and asexual reproduction through fragmentation, where a portion of the plant breaks off and continues to grow as a new plant. |

Naiads

| Common Name: | Naiads |

| Scientific Name: | Najas spp. |

| Native or Non-native: | Native, except for N. minor which is non-invasive. |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images of Common water nymph ( Najas guadalupensis) Click here for more images of Spiny naiad (Najas minor) |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Najadaceae |

| Distribution: | Four naiad species occur in Chesapeake Bay. The first two are more common than the latter two. Najas guadalupensis (southern naiad or bushy pondweed) Najas minor (no common name) Najas flexilis (northern naiad) Najas gracillima (slender naiad). Naiads are native except for N. minor which was introduced from Europe. Naiads grow primarily in lakes and freshwater portions of Chesapeake Bay tributaries. Bushy pondweed tolerates slightly brackish water. Naiads can tolerate a wide variety of substrates and tolerate relatively low light. |

| Recognition: | Naiads vary in size from inch-high tufts on sandy bottoms to highly branched plants three to five feet tall on silty bottoms. In general the naiads have slender, branching stems with narrow leaves that broaden at the base and are opposite or in whorls. Naiads have small, fibrous roots without rhizomes or tubers. The four species in Chesapeake Bay resemble one another, however, their leaves provide distinguishing characteristics. Bushy pondweed and northern naiad have wider leaves than the other two species. Southern naiad leaves are flat and straight, whereas leaves of northern naiad curve out from the stem at maturity. Slender naiad and N. minor have slender leaves with a truncated (abruptly-ending) basal sheath. N. minor is distinguished from slender naiad by stiff, recurved leaves and lengthwise ribs on its seed coat. Slender naiad has minute leaf-margin teeth that are difficult to see, whereas leaf-margin teeth of N. minor are visible to the naked eye. |

| Ecological Significance: | N. guadalupensis and N. flexilis are considered to be excellent food sources for waterfowl. All parts of the plants (stems, leaves and seeds) are eaten by a variety of waterfowl including lesser scaup, mallards and pintails. The other two species of Naiads are less important due to their scarcity (N. gracillima) and low nutritional value (N. minor). |

| Similar Species: | Naiad species are similar in appearance and misidentifications are common even for experts unless plants are fully developed. All except for N.minor are difficult to distinguish without the use of a handheld lens and some experience. |

| Reproduction: | Reproduction occurs primarily by seed in late summer. Male and female flowers are located on leaf axils. Seed germination and plant growth occur in late spring. The seeds that develop after pollination have surface markings, and each species has its own characteristic markings. |

Parrot Feather Milfoil

| Common Name: | Parrot Feather Milfoil |

| Scientific Name: | Myriophyllum brasiliense (or aquaticum) |

| Native or Non-native: | Non-native |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Hydrocharitaceae |

| Distribution: | Parrot feather is a herbaceous aquatic perennial that gets its name from the feather-like appearance of its gray-green leaves. Male and female flowers are on different plants, but only the female plants have been found in North America. Parrot feather is a native of the Amazon River and was introduced to North America in the Washington, D.C. area around 1890. However, since its introduction, the plant has spread throughout the southern United States. It is found in non-tidal fresh waters, where it can quickly spread to cover available habitat. It has not been reported in tidal waters and its salinity tolerance is not known. |

| Recognition: | Plants are reddish tinted with bright green growing tips. Very leafy foliage on stout stems that often emerge a few inches above water (emergent tips appear gray-green). Leaves occur in whorls of mostly 5, all alike, 2-5 cm (< 3/4 in to 2 in) long with 10-25 hair-like segments per side. Bracts are leaf-like, with filiform bracteoles (thread-like leaves) cleft into 2 or 3 divisions. Parrot feather bears fruits that are 2 to 3 mm (1/16 in) long, and finely granular. |

| Ecological Significance: | Parrot feather can grow in many different water habitats, but grows best in deeper, nutrient-rich environments. Parrot feather can spread and grow very quickly, which can have adverse effects on the body of water it is in, such as inhibiting water flow, and reducing the amounts of dissolved oxygen in the water which can be harmful for fish. Also, since it can spread so quickly, it can outcompete other SAV like pondweeds and coontail which are good sources of food for waterfowl. |

| Similar Species: | Parrot feather usually has whorls of 5 pinnate leaves, whereas Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) usually has whorls of 4 pinnate leaves and only its flowers stick above the water. Appearance is similar to coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum); coontail, however, has whorls of 9-10 leaves at stem nodes, lacks a root system and never protrudes above the water surface. |

| Reproduction: | Reproduction is both sexual (by seed) and asexual (by fragmentation). Parrot feather is dioecious with unisexual flowers, which form in the axils (the angle between the upper side of the leaf and the stem) of submerged leaves. |

Pondweeds

| Common Name: | Pondweeds |

| Scientific Name: | Potamogeton sp. |

| Native or Non-native:: | Most are native species. |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images of Largeleaf pondweed (Potamogeton amplifolius) Click here for more images of Longleaf pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus) Click here for more images of Robbins' pondweed (Potamogeton robinsii) |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | |

| Distribution: | Cosmopolitan throughout MD in rivers, ponds, reservoirs and tidal freshwater to moderately brackish tributaries of Chesapeake Bay. Pictured is P. spirillus, one of the smallest of the Chesapeake Bay pondweeds.Some other pondweed species found in Maryland are Horned Pondweed (Zannichellia palustris), Curly Pondweed (Potamogeton crispus), Sago Pondweed (Stuckenia pectinata), Slender Pondweed(Potamogeton pusillus), and Illinois Pondweed (Potamogeton illinoensis). |

| Recognition: | Range in size from 0.1 to 2 meters tall, with leaves from 1 to 15 cm long. Most species have bimorphic leaves (two distinctly different leaf shapes on a single plant) and these leaves are arranged in an alternate, whorled, or opposite fashion going along the stem. Many species of pondweeds are extremely difficult to identify even for experts. |

| Ecological Significance: | Many species of pondweeds provide a food source for waterfowl, and as habitat and cover for fish and other aquatic organisms. Pondweeds are probably the most abundant non-tidal SAV found in the mid-Atlantic. |

| Similar Species: | This depends on the type of pondweed being observed. There are many different types with various distinct features. |

| Reproduction: | Primarily sexual reproduction by seed. |

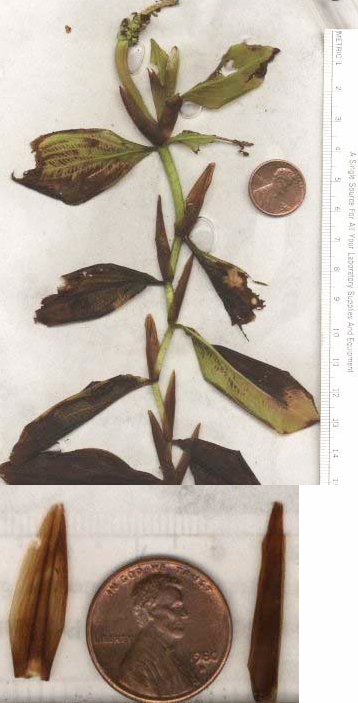

Redhead Grass

| Common Name: | Redhead Grass |

| Scientific Name: | Potamogeton perfoliatus |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Potamogetonaceae |

| Distribution: | Redhead grass is typically found in fresh to moderately brackish and alkaline waters. Redhead grass grows best on firm, muddy soils and in quiet water with slow-moving currents. The wide, horizontal leaves of redhead grass may be more susceptible to covering by epiphytic growth than those of other bay grasses. |

| Recognition: | Redhead grass is highly variable in its appearance and, in fact, two stems on a single plant may appear to be separate species. In relatively shallow water, for example, plants have thicker, darker green foliage than do plants growing in deeper water. Leaves of redhead grass are flat and oval-shaped, 1-7 cm (< 1/3 in to 2 ¼ in) long and 1-4 cm (1/3 in to 1 2/3 in) wide with parallel veination. Leaf margins are slightly crisped, and basal parts of leaves clasp straight and slender plant stems. Leaf arrangement is alternate to slightly opposite. Branching is more developed in the upper portion of the plant. Redhead grass has an extensive root and rhizome system that securely anchors the plant. |

| Ecological Significance: | Redhead grass probably got its common name from the redhead ducks often found feeding on it. Redhead grass is considered an excellent food source for waterfowl. It is also one of the most easily recognizable bay grass species in the bay because of its flat, oval-shaped leaves, the base of which are attached to the plant stem. |

| Similar Species: | Young shoots of redhead grass may be confused with curly pondweed (Potamogeton crispus). |

| Reproduction: | Asexual reproduction occurs by formation of over-wintering, resting buds at the ends of rhizomes. Sexual reproduction regularly occurs in early to mid-summer. Spikes of tiny flowers emerge from leaf axils on ends of plant stems. Flower spikes extend above the water surface and the pollen is wind-carried. As fruits mature they sink below the surface where they release seeds. Attempts to propagate plants from seed have been unsuccessful. |

Sago Pondweed

| Common Name: | Sago Pondweed |

| Scientific Name: | Stuckenia pectinata* |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for larger images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Potamogetonaceae |

| Distribution: | Sago pondweed is widely distributed in the United States, South America, Europe, Africa and Japan. In Chesapeake Bay, sago pondweed is widespread growing in fresh non-tidal to moderately brackish waters. It can tolerate high alkalinity and grows on silty-muddy sediments. It tolerates strong currents and wave action better than most bay grasses because of its long rhizomes and runners. |

| Recognition: | Thread-like leaves are 3 to 10 cm (1 ¼ in to 4 in) long, and 0.5 to 2 mm (1/32 in to 1/16 in) wide, and taper to a point. The basal sheath of leaves sometimes has a pointed tip or bayonet that aids in identification when plants are not in flower. Seeds form in terminalclusters. Stems are slender, and abundantly branched so that bushy leaf clusters fan out at the water surface. Roots have slender rhizomes, and are long and straight. |

| Ecological Significance: | Sago pondweed (* formerly Potamogeton pectinatus) is widespread throughout the United States and is considered one of the most valuable food sources for waterfowl in North America. Its nutrient filled seeds and tubers, as well as leaves, stems and roots, are consumed by numerous species of ducks, geese, swans and marsh and shorebirds. Sago pondweed beds are also excellent fish habitats. |

| Similar Species: | Horned pondweed (Zanichellia palustris) and widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima) have a very similar appearance to sago pondweed and are difficult to identify without fruits. Sago pondweed has alternately arranged leaves, but horned pondweed has oppositely arranged or whorled leaves. The leaves of widgeon grass are also alternately arranged but are not in bushy clusters like those of sago pondweed. The seeds are also distinctly different among the three species. Sago pondweed seeds are in terminal clusters. Wideon grass has single seed pods that form at the base of fan-shaped clusters of short stalks, and horned pondweed seeds occur in groups of 2-4, are horn-shaped pairs and form in the leaf axils. |

| Reproduction: | Reproduction is by seed formation and asexual reproduction. Sexual reproduction occurs during early summer by formation of a spike of perfect flowers that appear like beads on the slender stalk. Flowers release pollen that floats on the water surface, resulting in fertilization. Developing seeds remain on the rachis of the spike until autumn when they are dispersed into the water. The germination rate is low, however, and asexual reproduction is more significant. Asexual reproduction is by two kinds of starchy tubers: 1) tubers produced at ends of underground rhizomes and runners, or 2) another tuber that forms in leaf axils and at end of leaf shoots; these later sink to the substrate. Both kinds of tubers grow singularly or in pairs, and can form plants later in spring. |

Slender Pondweed

| Common Name: | Slender Pondweed |

| Scientific Name: | Potamogeton pusillus |

| Native or Non-native: | Native |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Potamogetonaceae |

| Distribution: | Slender pondweed grows in fresh to slightly brackish water. It grows in soft, fertile mud substrates and quiet to gently flowing water. Slender pondweed occurs in many ponds, lakes and both tidal and non-tidal waters in the Mid-Atlantic. |

| Recognition: | The leaves of slender pondweed are narrow, linear and grass-like, and are arranged alternately on slender, branching stems. Leaf blades of slender pondweed are entire and have pointed tips and can have a purplish tint. The leaf bases are free of stipules and usually contain two small translucent glands. Slender pondweed has a root-rhizome system. |

| Ecological Significance: | Like all other pondweeds, slender pondweed is considered an important food for waterfowl. Its ability to colonize a wide range of habitats make it one of the more common species in Maryland. Slender pondweed is also a good habitat for fish. |

| Similar Species: | Slender pondweed is similar in appearance to sago pondweed (Stuckenia pectinata), widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima) and horned pondweed (Zannichellia palustris). However, slender pondweed only overlaps in distribution with horned pondweed. Slender pondweed has slightly wider and longer leaves. |

| Reproduction: | Slender pondweed reproduces asexually and sexually. Asexual reproduction is by buds, which are dense aggregations of leaves that eventually drop off and over-winter to form new plants in spring. Smooth-leaved winter buds form axillary along branches and at terminal ends of stems. Sexual reproduction is by late summer flowering. These flowers occur in whorls of 3 to 5 on terminal or axillary spikes. Fertilization takes place underwater, producing smooth seeds with rounded backs. |

South American Elodea

| Common Name: | South American Elodea / Brazilean Waterweed / Brazilean Elodea / Anacharis |

| Scientific Name: | Egeria densa (formally Elodea densa) |

| Native or Non-native: | Non-native species. |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Hydrocharitaceae |

| Distribution: | South American Elodea (Egeria Densa) is an invasive submerged aquatic plant that originally came from South America, and is often referred to as Brazilian Waterweed. This aquatic plant is now found throughout the United States due to its potential for fast growth and rapid spreading. It is a freshwater plant that can grow in lakes, ponds, streams, and ditches. It is not common in Maryland but it is known from a few locations. |

| Recognition: | South American Elodea is a rooted plant with a many-branched stem. It has many leaves, which are longer than they are wide. The leaves have finely toothed margins and are grouped in whorls of ~4. The stem and leaves are bright green, and the many branches of the plant gives it a bushy appearance. |

| Ecological Significance: | Since it can grow and spread at such a high rate, South American Elodea can end up displacing native species and taking over areas, which lowers biodiversity and can have negative effects on the ecology. Another issue that it can cause is that if too much of the plant grows in one stream it can change the flow of the water which also can impact the ecology inside and around that stream. |

| Similar Species: | South American Elodea is easily confused with Hydrilla and Common Waterweed because they all have whorled, green leaves with a somewhat bushy appearance. The easiest way to tell the difference between these plants is the amount of leaves per whorl, as South American Elodea usually has four while Hydrilla has 5 and Common Waterweed generally has 3. |

| Reproduction: | The main method of reproduction for the plant is vegetative, meaning that new plants can grow from broken off fragments of another plant. Even though the plant does have male and female flowers, there have been no recorded cases of seed germination in the United States, and the only way the plant has been seen to reproduce has been through vegetative reproduction. |

Brazilian Waterweed

| Common Name: | South American Elodea / Brazilean Waterweed / Brazilean Elodea / Anacharis |

| Scientific Name: | Egeria densa (formally Elodea densa) |

| Native or Non-native: | Non-native species. |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Hydrocharitaceae |

| Distribution: | South American Elodea (Egeria Densa) is an invasive submerged aquatic plant that originally came from South America, and is often referred to as Brazilian Waterweed. This aquatic plant is now found throughout the United States due to its potential for fast growth and rapid spreading. It is a freshwater plant that can grow in lakes, ponds, streams, and ditches. It is not common in Maryland but it is known from a few locations. |

| Recognition: | South American Elodea is a rooted plant with a many-branched stem. It has many leaves, which are longer than they are wide. The leaves have finely toothed margins and are grouped in whorls of ~4. The stem and leaves are bright green, and the many branches of the plant gives it a bushy appearance. |

| Ecological Significance: | Since it can grow and spread at such a high rate, South American Elodea can end up displacing native species and taking over areas, which lowers biodiversity and can have negative effects on the ecology. Another issue that it can cause is that if too much of the plant grows in one stream it can change the flow of the water which also can impact the ecology inside and around that stream. |

| Similar Species: | South American Elodea is easily confused with Hydrilla and Common Waterweed because they all have whorled, green leaves with a somewhat bushy appearance. The easiest way to tell the difference between these plants is the amount of leaves per whorl, as South American Elodea usually has four while Hydrilla has 5 and Common Waterweed generally has 3. |

| Reproduction: | The main method of reproduction for the plant is vegetative, meaning that new plants can grow from broken off fragments of another plant. Even though the plant does have male and female flowers, there have been no recorded cases of seed germination in the United States, and the only way the plant has been seen to reproduce has been through vegetative reproduction. |

Watercress

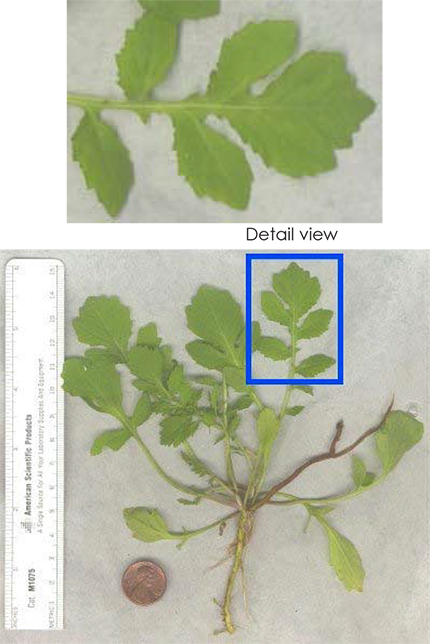

| Common Name: | Watercress |

| Scientific Name: | Nasturtium officinale |

| Native or Non-native:: | Non-native |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Distribution: | Originally native to Eurasia, but now common in streams and wet areas throughout Chesapeake Bay. It will grow either floating on the surface of the water, submerged, or spread over muddy surfaces in very shallow water. |

| Recognition: | A coarse, much branched member of the mustard family with deeply divided compound leaves and a low-growing growth form. Often quite dense in small streams of suitable habitat. The leaves are small and round, and when the plant is flowering it produces small, white flowers that grow in clusters. |

| Ecological Significance: | Watercress is a possible food source for the organisms living near it, and is prized for its spicy flavor and often cultivated or foraged from the wild and eaten by humans. Like most SAV species it can provide shelter for small organisms in the water. Can potentially alter the flow of the water that it is in due to dense growth, and in extreme cases even temporarily impede the flow |

| Similar Species: | None. |

| Reproduction: | Mostly sexual reproduction by seed, but it has been found to be able to reproduce asexually through vegetative reproduction. |

Water Stargrass

| Common Name: | Water Stargrass |

| Scientific Name: | Heteranthera dubia |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Pontederiaceae |

| Distribution: | Water stargrass can be found in non-tidal freshwater areas of tributaries, and in streams, lakes and ponds. Water stargrass is found in many parts of Chesapeake Bay as well as in some rivers and reservoirs. It grows primarily in clay or calcareous soils, but also in gravel streams and rivers. Water stargrass can tolerate moderately eutrophic waters. A terrestrial form of water stargrass with waxy cuticle can also be found when low water levels strand plants on shore. |

| Recognition: | Water stargrass has grass-like leaves with no distinct midvein. Leaves are arranged alternately on freely-branching stems, with the basal parts of the leaf forming a sheath which wraps around the stem. In summer, water stargrass produces striking, yellow star-like flowers that protrude well above the water surface. The terrestrial form also produces flowers, but branching of stems is reduced or absent and leaves are small or leathery. |

| Ecological Significance: | Unlike other bay grasses, water stargrass also has a terrestrial form that develops when low water levels strand the plant (the origin of its other common name, mud plantain). Water stargrass is sometimes eaten by waterfowl, and also provides habitat for micro/macro invertebrates which are in turn eaten by other organisms such as fish and waterfowl. |

| Similar Species: | The leaves of water stargrass are similar in appearance to those of the Naiads (Najas spp.), though the leaves of water stargrass are much longer. |

| Reproduction: | Reproduction of water stargrass is by sexual and asexual means. During sexual reproduction yellow flowers arise from a six-lobed spathe with a long thread-like tube. Flowers that do not reach the water surface remain closed and self-pollinate. Seeds are produced over the winter months and germinate in spring. Asexual reproduction occurs throughout the growing season by creating new plants from broken stem fragments. Water stargrass becomes dormant in winter, and stems and broken stem tips remain in the sediment until spring. |

Water Starwort

| Common Name: | Water Starwort |

| Scientific Name: | Callitriche spp. |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Callichtrichaceae |

| Distribution: | Water starworts are widespread, usually in very shallow, quiet non-tidal fresh waters, and are found in all 49 continental states. Water starworts can also be found occasionally in protected tidal waters. |

| Recognition: | Water starworts are small plants with very bright green leaves. The leaves are obovate to oval in shape and are 2 cm long and 3 to 8 mm wide. When it grows on mud in low-water conditions, the leaves of water starwort are oblong. Upper leaves of the plants are obovate to oval and are often floating or emergent. The genus Callitriche also includes one terrestrial species (C. deflexa). |

| Ecological Significance: | Water starwort provides important habitat for small reptiles and amphibians, as well as a spawning platform for fish. It also provides a food source for waterfowl through its leaves and berries. May cause problems if too much is growing in an area by crowding out other plants and causing shade in the water which makes it hard to grow under. |

| Similar Species: | When underwater and without flowers or seeds, the water starworts can resemble common waterweed (Elodea canadensis). Water starwort, however, has only two leaves at each joint whereas the leaves of common waterweed grow in whorls of 3. |

| Reproduction: | Flowering occurs in July to September. Small flowers grow together in groups of 1 to 3, without perianth, in the axils of leaves; these form numerous seeds closely set within the leaf axils. |

Widgeon Grass

| Common Name: | Widgeon Grass |

| Scientific Name: | Ruppia maritima |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Ruppiaceae |

| Distribution: | Widgeon grass tolerates a wide range of salinity, from the slightly brackish upper and mid-Bay tributaries through near-seawater salinity in the lower Bay and even in hypersaline salt pannes. Widgeon grass has also been reported to grow in the freshwater parts of some estuaries and in non-tidal waters. In more saline lower Chesapeake Bay, widgeon grass is by far the dominant bay grass. Widgeon grass is most common in areas with sandy substrates, although it occasionally grows on soft, muddy sediments. High wave action can damage the slender stems and leaves of widgeon grass. |

| Recognition: | Short, linear, thread-like leaves are 3 to 10 cm (1 ¼ in to 4 in) long and 0.5 mm (<1/32 in) wide. Leaves are arranged alternately along slender, branching stems. Leaves have a sheath at the base and a rounded tip. Widgeon grass has an extensive root system of branched, creeping rhizomes that lack tubers. There are two growth forms of widgeon grass in Chesapeake Bay: an upright, highly branched form present during flowering (summer); and a creeping growth form with the leaves appearing basal from early spring through later winter. |

| Ecological Significance: | Widgeon grass populations tend to fluctuate significantly from year to year. Multi-acre beds often appear one year and disappear the next. Within the growing season, widgeon grass also grows and dies back quickly compared to other species- often appearing in May and being nearly completely gone by the end of August. Despite it's ephemeral nature, Widgeon grass is one of the more valuable waterfowl food sources for waterfowl and all parts of the plant have excellent nutritional value. Widgeon grass is also important for its ability to tolerate a wide range of salinity. In higher salinity water, widgeon grass is often found growing together with eelgrass, with the widgeon grass more common in shallow areas and the eelgrass more common in deeper water. Widgeon grass can also be found growing in ditches alongside roads and agricultural fields where it derives its other common name, ditch grass. Widgeon grass is an important and easily accessible habitat for many micro and macro invertebrates and some small fish. |

| Similar Species: | When not in flower or with seeds, widgeon grass closely resembles horned pondweed (Zanichellia palustris) and sago pondweed (Stuckenia pectinata). Unlike widgeon grass, however, horned pondweed has opposite to whorledleaves, and the leaves of sago pondweed are in bushy clusters. When in seed, the single seed pods that form at the base of fan-shaped clusters of short stalks distinguish widgeon grass. Sago pondweed seeds are in terminal clusters, and horned pondweed seeds occur in groups of 2-4, are horn-shaped and form in the leaf axils. |

| Reproduction: | Widgeon grass reproduces asexually and sexually. Asexual reproduction occurs by emergence of new stems from the root-rhizome system. Sexual reproduction in late-summer produces two perfect flowers enclosed in a basal sheath of leaves. The flowers extend towards the water surface on a peduncle or flower-stalk. Pollen released from stamen float on the water surface until contacting one of the extended pistils. Fertilized flowers produce four black, oval-shaped fruits with pointed tips. Individual fruits extend on stalks, which occur in clusters of eight stalks. |

Wild Celery

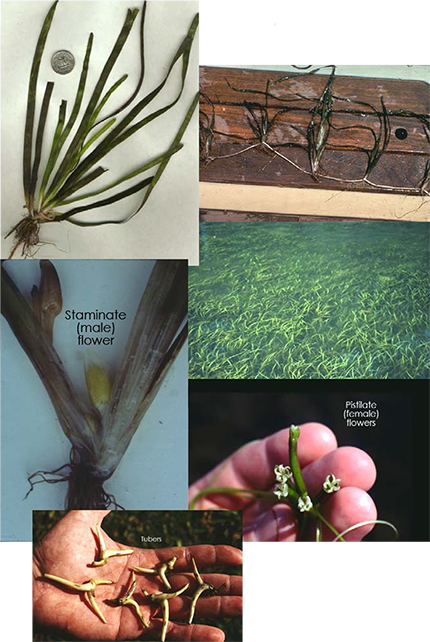

| Common Name: | Wild Celery |

| Scientific Name: | Vallisneria americana |

| Native or Non-native:: | Native to Chesapeake Bay |

| Illustration: |  |

| Link to larger illustration: | Click here for larger image. Click here for more images. |

| Printable Version: | Print out a copy for the field. |

| Family: | Hydrocharitaceae |

| Distribution: | Wild celery is found from the Atlantic Coastal Plain states west to Wisconsin and Minnesota. It is primarily a freshwater species. Wild celery seems to prefer coarse silty to sandy soil, and is fairly tolerant of murky waters and high nutrient loading. It can tolerate wave action better than some other bay grass species. Wild celery is cosmopolitan in Maryland and is common in rivers, lakes and throughout the freshwater regions of Chesapeake Bay. |

| Recognition: | Long, flattened, ribbon-like leaves arising from a cluster at the base of the plant are minutely serrate with bluntly rounded tips. Leaves grow to 1.5 m (5 ft) in length and approximately 1 cm (1/3 in) width. A light green stripe runs down the center of the finely-veined leaves. |

| Ecological Significance: | Wild celery is particularly valuable as a food source for waterfowl (Korschgen and Green 1998). For example, the scientific name for the canvasback duck (Aythya valisineria) is derived from its association with wild celery. Canvasback and other diving ducks such as scaups, scoters and redhead, rely on the winter buds and rootstocks of wild celery for food during migration and in their wintering habitats (Korschgen and Green 1998). |

| Similar Species: | Wild celery can be confused with eelgrass (Zostera marina). However, wild celery has a light green stripe in the center of its leaves and its leaves are much longer and wider than those of eelgrass. All wild celery leaves start at the base of the plant, whereas eelgrass leaves emerge alternately from a main plant stem. Because wild celery prefers lower salinity and eelgrass higher salinity, the two species do not co-occur in the same location. |

| Reproduction: | Sexual and asexual reproduction are both common. Asexual reproduction occurs when winter buds, or turions, form at the meristem of wild celery plants in late summer. These winter buds elongate in spring, sending a stolon to the surface from which a new plant emerges. During the growing season, each plant can send out rhizomes that grow adjacent to the parent plant. Sexual reproduction occurs in late July to September. Wild celery is dioecious and individual plants are either male or female. Individual pistillate flowers have three sepals and three white petals, and occur in a tubular spathe that grows to the water surface at the end of a long peduncle. Staminate (male) flowers are crowded into an ovoid spathe borne on a short peduncle near the base of the plant. Eventually the spathe of staminate flowers breaks free and floats to the surface where it releases its flowers. Fertilization occurs when male flowers float into contact with female flowers. When fertilization is complete the peduncle of the pistillate flower coils up and fruit develops underwater. Fertilization produces a long cylindrical pod containing small, dark seeds. |

Print out a complete version of the key in PDF format (Adobe Acrobat file 18MB)

For permission to reproduce individual photos, please contact Mike Naylor

The text and photos used in this key were produced through a collaborative effort among the following partners.